By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

A man stares across a war torn street as heavy fire falls down around him. Across the street, a young girl screams in tears, the remains of her family scattered around her. Dave Eubank hesitates where he is, for a split second, before running through the smoke toward the young girl, the future less certain than his natural impulse to save those trapped amid enemy fire.

This is the documentary Free Burma Rangers, but to understand Dave Eubank, you first need to understand the men bringing his story to life.

Chris Sinclair, Dallas-based photojournalist

Chris Sinclair, Dallas-based photojournalist

A photojournalist who grew up in Texas, then Colorado and North Carolina, Chris Sinclair discovered a love for Asia during a series of summer trips overseas. First Bangladesh, then Vietnam, Asia drew him in so strongly that he learned Mandarin and moved to China to explore the culture. As a journalist, he moved to China, bordering Burma. Later, he served as a correspondent based in Asia, going all over the world to each continent and sixty-plus countries.

Sinclair returned to the U.S., exploring his options with newspapers in Colorado and Utah, but Burma called to him. Googling Free Burma Rangers, he contacted Dave Eubank through the website, asking about access to refugees who he could interview about their experience in the civil war. Eubank invited him to come on a relief mission with them, so in 2004, Sinclair hiked at night through hours of water, witnessed life in far-off villages, and met people forcibly relocated by violence.

“I took pictures of little refugee families, huddled in orchards holding a bag of their possession and a little bag of rice,” he remembered, “just like today, people waiting to get into the country where they could seek refuge. It rocked my world.”

Sinclair moved permanently to Thailand from 2005 to 2011, but his job prevented him from returning to Burma. Still, he did some advocacy work with the FBR, before leaving the journalistic organization to return to the States for school. At Ohio University working toward his M.A. in Visual Communications, he decided to focus his Master thesis film project on the FBR.

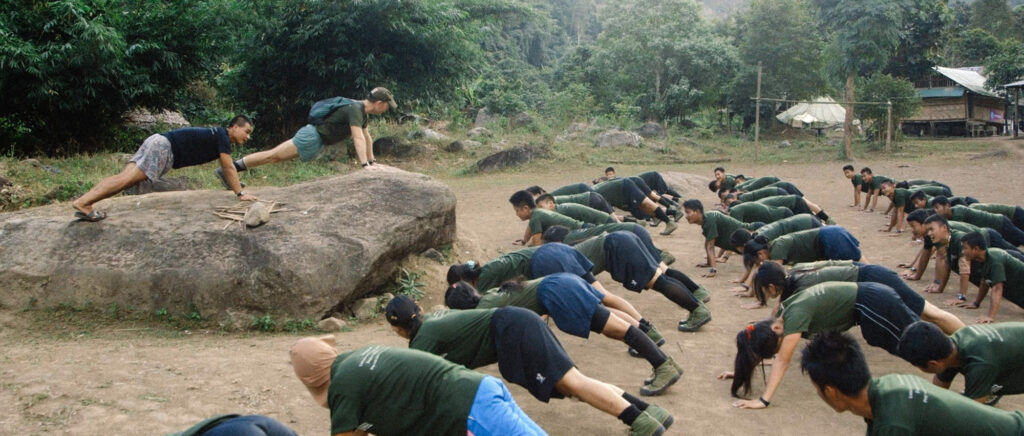

“It was focused on the people suffering, not featuring Dave Eubank and his family,” Sinclair explained. “The security situation is very precarious, and we didn’t want that to be jeopardized. He would avoid interviews, instead directing journalists to tell stories of IDPs and FBR relief teams, but he wanted to get the word out. So I focused on three different individuals going through the FBR training in Burma, a four-part series. While I was there filming for two months, Dave and I would be walking along the trail, discussing what a feature film could look like. I said, ‘If you ever decide to tell your story, let me know.’”

“It was focused on the people suffering, not featuring Dave Eubank and his family,” Sinclair explained. “The security situation is very precarious, and we didn’t want that to be jeopardized. He would avoid interviews, instead directing journalists to tell stories of IDPs and FBR relief teams, but he wanted to get the word out. So I focused on three different individuals going through the FBR training in Burma, a four-part series. While I was there filming for two months, Dave and I would be walking along the trail, discussing what a feature film could look like. I said, ‘If you ever decide to tell your story, let me know.’”

Sinclair says Eubank is a missionary, “a person who speaks about God at every opportunity no matter the environment he finds himself in” but also a warrior, “one who overcomes obstacles.” Having followed the FBR founder off and on for years, he proposes that Eubank is a warrior, but one who only tackles battles that exist in front of him, not looking for one. Eubank operates from principles, Sinclair says, like “Don’t be led by comfort or fear, they’re lousy guides” and “Don’t ask what will become of me, because that’s from a position of fear.” But Sinclair adds, it’s also always from a viewpoint that sees people suffering and refuses to find a safe hiding place.

Sinclair says that their common Christian faith allowed the two men to talk about what the film would look like. Too often, the media had run stories about the FBR that seemed to ridicule the organization for being both Christian aid and armed soldiers. Sinclair watched as Eubank measured every decision in prayer, all the time, whether it was violent or peaceful, large or small. Both Eubank and Sinclair saw an opportunity to thank God for what God was doing in Burma and around the world.

“The finished film is outgrowth of partnership between Dave Eubank and I. I’ll help you if you want to be the guy to start telling me the story. I didn’t know which end was up; I just knew you needed to film everything.”

By 2013, the two men were touring around the United States and Burma as well, filming actual events over four Burma missions that resulted in hundreds of hours of work. By 2013, Deidox Films saw some of Sinclair’s footage and asked about joining forces to tell the FBR story.

“We were sharing office space,” remembered the photojournalist. “I came from a very solitary, lone wolf photographer view point and they understood the film world and distribution. I’ve learned a lot and changed a lot over the production of the film. A lot of those lessons have been internalized and become part of how I think about everything now.”

“Brent is a story genius – he can see without bias where a loss of attention might happen, where setups and payoffs should happen. I knew none of that. As co-director, I knew who was who and how to get in touch with them. I was the bank for the who, what, where, when and why. There was a tight collaboration.”

Brent Gudgel, Documentary Director and Co-Founder of Deidox Films

Brent Gudgel, Documentary Director and Co-Founder of Deidox Films

The son of a pastor, Brent Gudgel left Azusa Pacific University with visions of Hollywood feature films and at twenty-three, he had a show on Hulu he wad directing. But after burning out on the Hollywood scene, he felt called in a different direction and took a job at a church. While working there, Gudgel made a deal with God that if the film world opened back up, that he would pursue filmmaking from God’s terms and not his own. Suddenly, Gudgel was tuned into stories that he says were better than anything he could’ve written or even known to go looking for.

As a child, he saw the struggles his father and other pastors went through week after week to make the gospel tangible in people’s lives, to move from “hearers to doers.” Already hooked on the idea that film could capture the public’s attention, he set out to see how film could help people process the gospel in ways that changed how they acted.

“Where did Christ tell disciples to do something without having to shown them? Because of the way our society is set up, we rarely get to see people practice what they preach. Our society is full of loud voices without action. One of the powerful things about documentaries is that they follow real people and show things actually happening. That changes the conversation, changes the game,” proposed Gudgel.

When Chris Sinclair shared the footage of all of the tours he had been on with the Free Burma Rangers, plus footage from other firsthand accounts of people embedded over the years and footage from the Rangers’ own cameras, Gudgel realized that there were twenty years, thirty thousand movie clips, and two thousand hours of material to edit down into a two-hour film. And Sinclair and Dave Eubank were trusting Gudgel and producing partner Dave Mahanes to edit it together.

“Normally in a documentary, you’re lucky if you get one great moment,” Gudgel explained. “In Free Burma Rangers, every scene is full of another great moment. You find yourself saying, ‘I can’t believe that just happened.’ Dave is like a character out of the Old Testament. He’s larger than life but also more human than ever. God uses him and his ministry built around the family in amazing ways.”

“Normally in a documentary, you’re lucky if you get one great moment,” Gudgel explained. “In Free Burma Rangers, every scene is full of another great moment. You find yourself saying, ‘I can’t believe that just happened.’ Dave is like a character out of the Old Testament. He’s larger than life but also more human than ever. God uses him and his ministry built around the family in amazing ways.”

There are two key things Gudgel hopes that people don’t miss. First, that Eubank and the FBR lead with love. He says it’s easy to think that these people are soldiers so they’re leading with guns, but after reviewing all the footage, it’s clear that they lead with love. Second, Gudgel says that if they didn’t have guns, the FBR would die – and that the ministry they provide to others would be impossible.

“To think about that and the ramifications, they’re the only aid organization on the front line in these situations. Sometimes, even the government is sitting down, and FBR are the only ones who are there. Everyone else is farther away.”

In one scene in particular, Gudgel remembers the FBR defending themselves with guns and grenades. He says that Eubank was adamant that the scene stay in the film, because if other soldiers watched the film and it wasn’t included, then they would know the film was flawed, edited to whitewash the FBR efforts. “Dave says there’s no way that we go there that this stuff doesn’t happen. The people they save would’ve never been saved because they’d be dead.”

Having had a front row seat to review years of the FBR’s work, Gudgel is clearly moved by what he’s seen. While each of the non-profit Deidox’s subjects lives out a real faith in a real world, he recognizes that the person of Dave Eubank challenges us to consider the risks a person of faith takes to follow Christ. “How willing am I to charge into the unknown not knowing how it will work out, if I know that’s what I’m supposed to be doing? Free Burma Rangers challenged me to consider what is really possible in faith.”

Free Burma Rangers will screen in select theaters via Fathom Events as a joint production by Deidox and Lifeway Films on February 24 and 25. You can find theaters and buy tickets here. For more on Deidox, check out their website or watch The Ordinance on Amazon Prime.