By Jacob Sahms

Tossing and turning in bed with a late-night tweak to a film has kept many directors from sleep, but such is not the case for James Whitehill. He’s been married to his writing partner Jess for most of two decades, thriving on their collaborative desire to tell stories that keep God at the center. While they eschew the title of “Christian filmmakers,” their first feature-length collaboration proves they’ve got soul – and a worldview that spans more than its fair share of the globe.

Whitehill has spent half of his thirty-eight years on the beaches of Australia, bouncing from birth to British private school, then back to Australia (where he wed Jess), and now back to rainy England to direct films. Over the course of an hour, he slides seamlessly between discussions of his beloved Newcastle United Magpies, the movement from producing Australian commercials to directing his feature-length film The 12, and working alongside Jess.

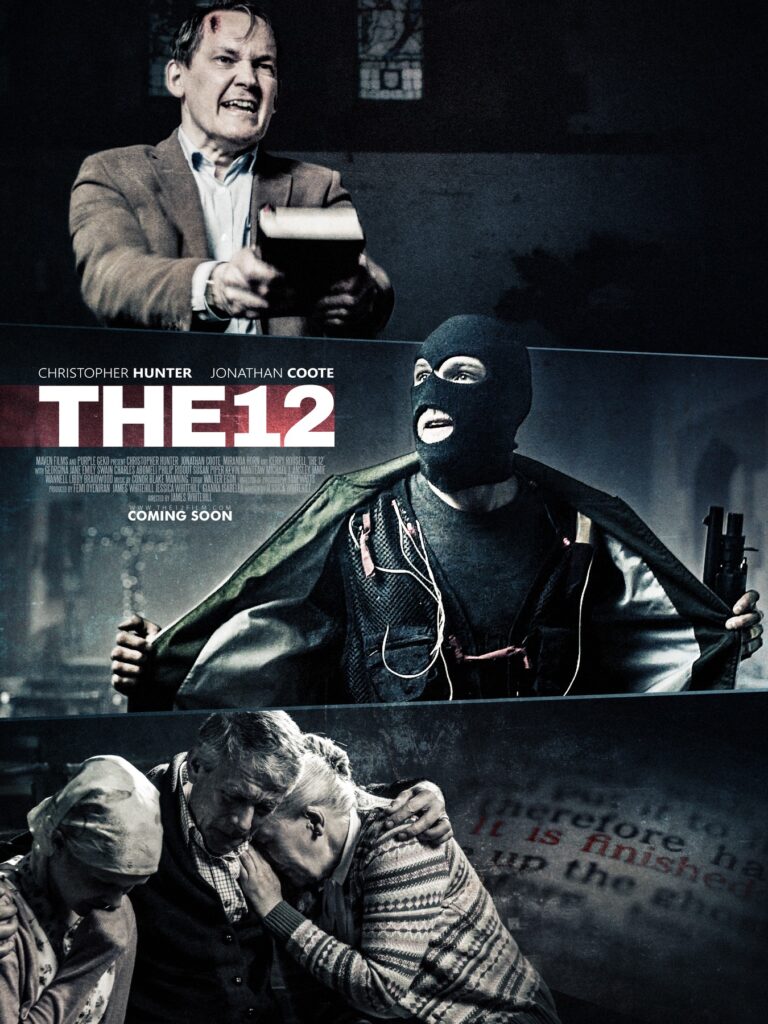

While the director has hung up his cleats, even as he’s inclined to coach from time to time, he’s fascinated by the discussions he’s shared at the pub, around a barbecue, or in the local church about faith and culture. Whitehill’s first film revolves around a gunman with a suicide vest named Caleb breaking into the countryside church where Pastor Mike presides over a quiet service. Caleb is angry, violent, and profane, hurting from his losses and his belief that church is full of liars and fakers worshipping a non-existent deity. For Americans, the violence can seem all too real given the rash of shootings in religious houses of worship, but Whitehill says it was a means to unpack what church is really like.

While the director has hung up his cleats, even as he’s inclined to coach from time to time, he’s fascinated by the discussions he’s shared at the pub, around a barbecue, or in the local church about faith and culture. Whitehill’s first film revolves around a gunman with a suicide vest named Caleb breaking into the countryside church where Pastor Mike presides over a quiet service. Caleb is angry, violent, and profane, hurting from his losses and his belief that church is full of liars and fakers worshipping a non-existent deity. For Americans, the violence can seem all too real given the rash of shootings in religious houses of worship, but Whitehill says it was a means to unpack what church is really like.

“England doesn’t have a gun problem, and neither does Australia. It’s just not an issue,” he explains. “The reception here is that the film is one people could share with their friends, Christian or non. Caleb is not from church – it’s not his faith, not his world. You take someone captive with a shotgun and a suicide vest, you’re not worried about your language. Everyone else who is in the church doesn’t do that, so we’ve put a line between the church and the not.”

It’s that demarcation the Whitehills are aiming for – that there is real-life hurt and pain outside (and sometimes inside) the church, but that the church can show up and model something different. The script and its direction refuse to blink in the face of that reality, because the couple wanted to make a film that exhibited what they believe about Jesus without watering down the hurt that the gospel invades.

It’s that demarcation the Whitehills are aiming for – that there is real-life hurt and pain outside (and sometimes inside) the church, but that the church can show up and model something different. The script and its direction refuse to blink in the face of that reality, because the couple wanted to make a film that exhibited what they believe about Jesus without watering down the hurt that the gospel invades.

Whitehill explains, “In our experience, the faith films have always had a really nice message but lacked the connective tissue for the everyday person. I read an article that a faith-based film will do well at the cinema but will review poorly. I want to make films that are great films, that are entertaining and make money, but don’t have to keep it PG. I don’t personally believe that you’re going to show someone a film and get them into the kingdom, converting them by showing them a movie. I want to make a great film people will connect with, and plant a seed that ‘there is a God, or there is a Jesus.’”

Whitehill explains, “In our experience, the faith films have always had a really nice message but lacked the connective tissue for the everyday person. I read an article that a faith-based film will do well at the cinema but will review poorly. I want to make films that are great films, that are entertaining and make money, but don’t have to keep it PG. I don’t personally believe that you’re going to show someone a film and get them into the kingdom, converting them by showing them a movie. I want to make a great film people will connect with, and plant a seed that ‘there is a God, or there is a Jesus.’”

To make the film, the Whitehills pulled from their extensive background, and the team of filmmakers and actors they assembled for five days of filming. Whitehill had a decade of producing commercials, with an expertise in production lacking the lavish budgets of American advertisements. Jess had run a kids’ drama school, directing three-hundred students a week from the plays she wrote weekly for each age group. Together, they mapped out line by line where their theater-based actors would stand and move so that dozens of pages could be shot with one take.

Nigerian-British actor and producer Femi Oyeniran came on board, bringing his experiences from Kidulthood, a British drama about growing up young and poor, and films like It’s a Lot and The Intent, which he wrote, directed, and produced. His connections allowed the Whitehills to focus on making the film, as Oyeniran raised the funds quickly to provide the means to make the film.

Nigerian-British actor and producer Femi Oyeniran came on board, bringing his experiences from Kidulthood, a British drama about growing up young and poor, and films like It’s a Lot and The Intent, which he wrote, directed, and produced. His connections allowed the Whitehills to focus on making the film, as Oyeniran raised the funds quickly to provide the means to make the film.

Cinematographer Tom Watts joined the team three weeks before they began filming, and his music video background shows up in the lyrical flow of many of the scenes. Influenced by the Baroque, Watts’ art background influenced how he lit the shots, and the focus on the characters against the backdrop of Jess’ production design. Whitehill’s hope was that they would produce a film comparable to some of his favorite shots from director Christopher Nolan’s films, telling Watts, “I want it to come across like it was shot by Chris Nolan’s nephew!”

Shot in May 2017, the final production was wrapped by October and the Whitehills delivered their completed project to the American Film Market. Turnkey Films believed the trailer was worthy of a deal with Netflix, and the Whitehills knew that a group of unknowns would not receive the theatrical run to justify the efforts. When Netflix ultimately passed on the project, Turnkey directed Whitehill to Amazon, where it arrived just a few weeks ago. It’s there that the director hopes it will stir people, entertaining them but also challenging them to ask questions as they walk away from a viewing.

“I like to think that I speak two languages,” Whitehill reflects. “I grew up in the church with ‘Christianese’ down pat, but having gone to regular school, regular university, and operating in the real world, I know that world, too. I’m happy to admit that some guys don’t know that I’m a Christian or that I go to church because I know people have preconceived ideas about church.”

“I like to think that I speak two languages,” Whitehill reflects. “I grew up in the church with ‘Christianese’ down pat, but having gone to regular school, regular university, and operating in the real world, I know that world, too. I’m happy to admit that some guys don’t know that I’m a Christian or that I go to church because I know people have preconceived ideas about church.”

“With The 12, Jess and I wanted to show people that the church is a beautiful room made up of imperfect people, striving to give their all and make the best effort of this one life they’ve got. I wanted people to see that there’s a single mom with two kids, an organist who likes vodka, an aging spinster marrying someone she met on the internet, the pastor’s kid with all the stereotypical problems. They’re real people who exist, with stories you could walk into any church and hear, as the microcosm of the faith. We believe the average Joe could walk in and say well this isn’t what I thought church was.”

A gunman, a congregation, and a chance to love. The 12 is a radical parable about hospitality and the possibility of forgiveness, streaming now on Amazon.