By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

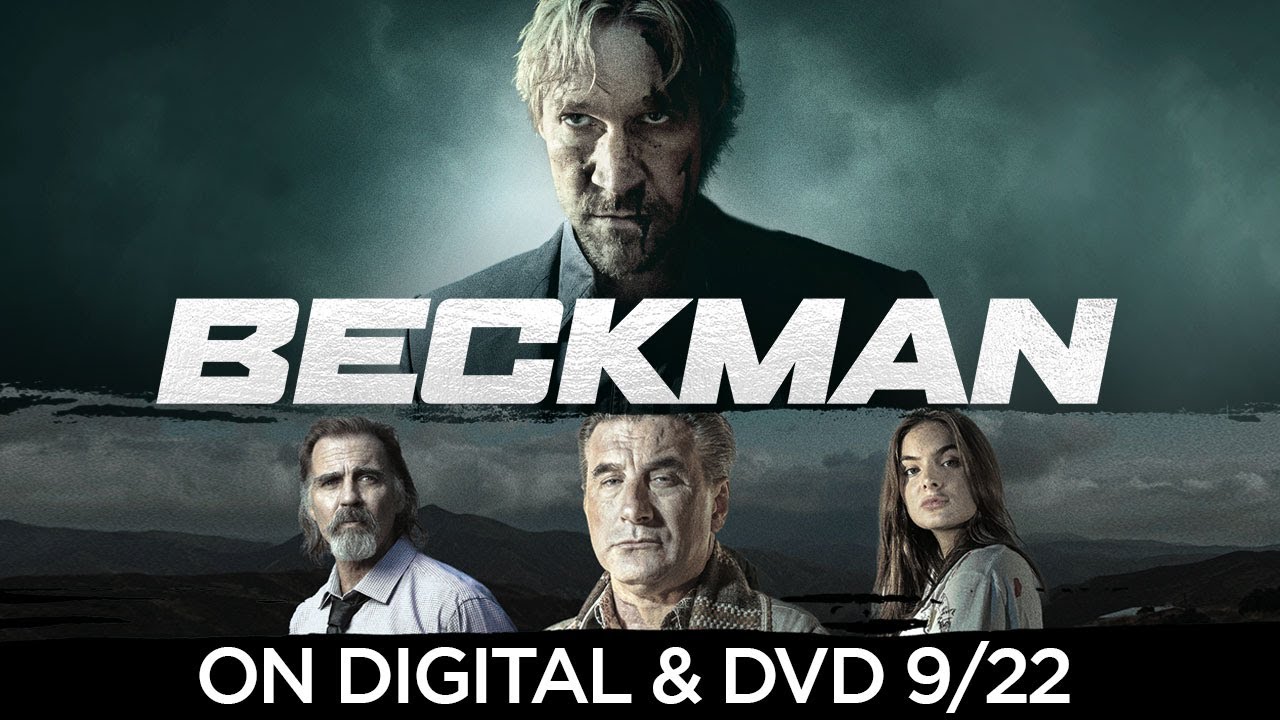

With films like The Dancer and the Dame and Samson on his resume, one might think that director Gabriel Sabloff has a “type” of film, but when Sabloff and David A.R. White get together, it’s usually been more apocalyptic (three Revelation Road films). So maybe we shouldn’t be surprised by their latest collaboration, a gun-heavy story of a retired assassin’s quest to free an orphaned teenager from the clutches of a cult leader. It’s not the typical fare for the Pure Flix founder and his action film director, but it’ll certainly appeal to his fans looking for a new take on the crime noir.

White stars as the titular Beckman, an assassin who flees the old life he lived, struggling with guilt from his past. Stumbling into the chapel of a pastor (Jeff Fahey) in need of encouragement, Beckman is “adopted” into the family of faith and ultimately becomes the pastor of the church. He grows attached to Tabitha (Brighton Sarbino), who has her own past to wrestle with, namely the cult leader Reese (a truly creepy William Baldwin). When Reese kidnaps Tabitha, Beckman goes on a bloody rampage through the underlings who helped with the kidnapping, leading to a final showdown with Reese.

The film clearly has some things it’s trying to do. It reinvents what we expect of White, making him a more athletic version of the characters he’s played, complete with choreographed fight scenes and growled lines. It also pushes the limits of what the Pure Flix audience is used to seeing, with gunshots, stabbing, and human trafficking taking place on screen. In the last regard, the film certainly has a few things to say about the complicit behavior by people up and down the pattern of abuse that leads to people, especially women, being sold for others’ pleasure. But while it attempts to channel the vibe of a film like Taken with a faith-based element, it muddies the water without providing a payoff that really sells the film.

The script from Sabloff doesn’t allow Beckman to really exhibit character development, or signs of integrating faith into his life. What happens in the final act doesn’t actually undo or redirect the people that he’s had to kill along the way to get to Reese. In a film like Taken, the audience expects the body count, because the tagline doesn’t encourage us to consider how Liam Neeson’s operative will come to terms with new faith and his violent ways. For Beckman, who is now a pastor, to punch, kick, and shoot his way through video game-like levels of bad guys, the audience has to ignore that he’s been a pastor for what feels like a minute.

Maybe Christians want a Beckman who will take out human traffickers like this, because it’s entertaining and more than a little Old Testament in nature. But the idea that a Christian pastor would go on a rampage, however justified, without contacting the police or seeking help, just feels like an excuse to have a shoot-em-up and call it Christian. By the time the audience gets to a place where the evil of human trafficking is presented as “the issue,” it’s a justification for violence, rather than a call to action. Ultimately, the film fails to give us the final payoff – either from the redemptive story of a man fighting for a woman left for dead or the redemptive story of God’s dramatic work of changing a life of violence to one of peace.