By Jacob Sahms

When writer/director Stephen Chbosky saw Dear Evan Hansen on Broadway three years ago, he recognized a kinship between the title character and Logan Lerman’s Charlie in Chbosky’s film Perks of Being a Wallflower. In fact, in the original novel Chbosky wrote, Charlie writes to a friend about his experience during his freshman year of high school… and it’s a letter to himself that sets up Evan Hansen for the disaster that follows. But the director says it’s not the hope that comes later that he focuses on with each of his projects, the life-giving light that he’s experienced audiences choose after seeing these movies.

“When I went to high school, before the internet, I wasn’t surprised by the public face and the private face that people wore,” Chbosky explains, “because there are the parts of us that are secrets we keep, and the more accessible parts that we think are acceptable to throw out for others to see. Now, the private and public selves are much more accessible, with the internet. There’s a permanent record. A mistake a fifteen-year-old person makes causes them to lose a job twenty years later. It’s a scary time for people.”

“The message of Dear Evan Hansen is to be yourself, no hiding, no lying, that you’re enough.”

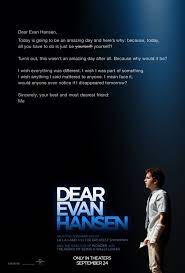

In the latest film by the director of Wonder and the screenwriter of the cinematic version of Rent and Beauty and the Beast, outcast and high school senior Evan Hansen writes himself a letter at the instruction of his counselor, to try and deal with his own anxiety. The letter ends up in the hands of another young man, who commits suicide, still possessing Hansen’s letter. After a series of misunderstandings where people assume the dead teenager wrote Hansen the letter, Hansen finds himself selling the lie, providing a charade of proximity to the teenager’s family and engendering sympathy in his peers.

In the latest film by the director of Wonder and the screenwriter of the cinematic version of Rent and Beauty and the Beast, outcast and high school senior Evan Hansen writes himself a letter at the instruction of his counselor, to try and deal with his own anxiety. The letter ends up in the hands of another young man, who commits suicide, still possessing Hansen’s letter. After a series of misunderstandings where people assume the dead teenager wrote Hansen the letter, Hansen finds himself selling the lie, providing a charade of proximity to the teenager’s family and engendering sympathy in his peers.

“When I saw the musical, I thought it was for all ages,” admits the director. “It’s for young people trying to form identity, and for parents trying to understand what this younger generation is facing. I can’t imagine dealing with this in the social media age, and I wanted to create a conversation starter for families. It’s a glimmer of hope for young people about making a bad choice and your life not being over.”

At a recent panel, Chbosky sat with health care professionals like psychologists and psychiatrists who shared how people lose hope when they think their lives are over. Too many people are losing hope, Chbosky knows, and he wants to point them back toward the light in the world, toward hope.

“The world would be a better place in every measure I could possibly think of if people chose forgiveness, second chances, the truth after a lie,” he muses. “I remember talking to Ben Platt about the two sets of lies Evan is dealing with. If only he would forgive himself, maybe people would learn to forgive him.”

“I wish our society would embrace forgiveness, embrace hope. I don’t remember when the world became so intolerant. We know that there is no redemption without sin, light without darkness. So I was very proud to make a movie of an understandable, relatable kid who does something terrible but ultimately owns up to it.”

It’s personal for the writer/director who is also husband and father. “I have a nine year old and six year old, and some of the media that comes at them through the algorithms, through TikTok or Youtube… You can’t keep it away even if you try at home because they have friends and it’s everywhere. I take pride in creating art that can inspire and instruct, give hope and comfort. I believe you do this to help, to find ways to get the conversation going in the right direction. I want you to be able to put on the movie and know that something good is happening. As a parent, you turn around so often and go, ‘oh, stop, and turn it off!’”

It’s personal for the writer/director who is also husband and father. “I have a nine year old and six year old, and some of the media that comes at them through the algorithms, through TikTok or Youtube… You can’t keep it away even if you try at home because they have friends and it’s everywhere. I take pride in creating art that can inspire and instruct, give hope and comfort. I believe you do this to help, to find ways to get the conversation going in the right direction. I want you to be able to put on the movie and know that something good is happening. As a parent, you turn around so often and go, ‘oh, stop, and turn it off!’”

Thanks to the other projects that he has been associated with, like Perks and Wonder, Chbosky has been blessed to hear stories about how his work has impacted others. He cites people who not only found hope but literally chose to live after reading one of his books or seeing one of those movies, who now write to share about their adulthood and the families they’ve helped create. “We all preach in our own way,” he adds with a chuckle.

On the other hand, Chbosky knows that not everyone appreciates those stories, that the world in the last few years seems to be growing in what he calls “tribal rage at others.” “It’s troubling for me, someone who cares about people,” he explains. “There’s a circular firing squad, cancel culture. It’s difficult to watch.”

“Everyone has a story of empathy – no-brainer, should be applauded. To the critical community, why take a knife out when trying to do something good? I’m not doing it for money or accolades. These movies can change and save lives, change communities. I think of that little kid who might have facial deformities [like Auggie in Wonder], or their sibling who can see this work of art, or the kid who can consider what my mom did on the first day of school. We need to stop vilifying each other. On the whole, human beings are doing the best they can. If there’s a topic we don’t know or understand, we can grow, get better, show empathy, learn sympathy, share kindness.”

Dear Evan Hansen arrives in theaters on September 24.