By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

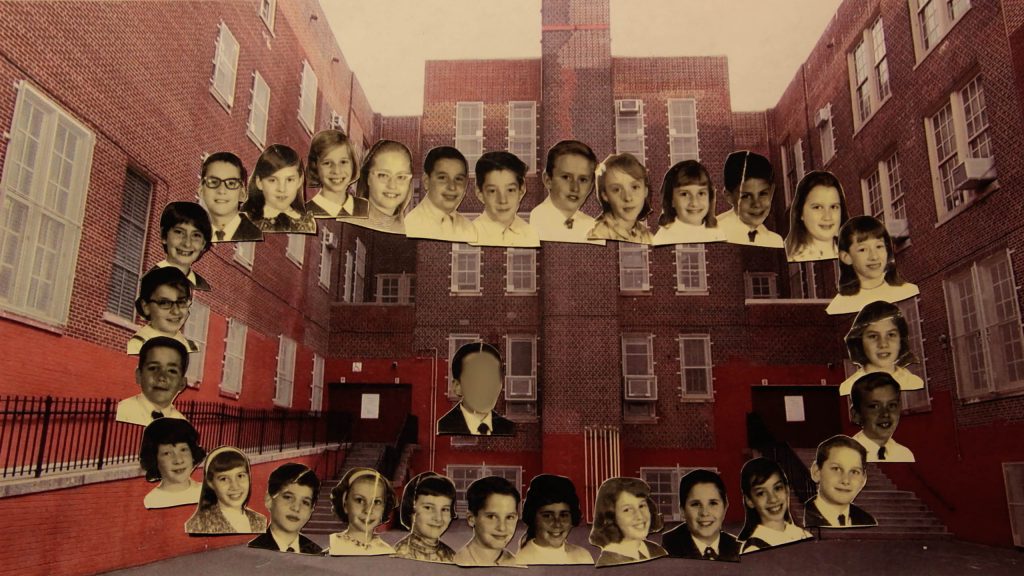

Director Jay Rosenblatt has delivered more than thirty films to screen, eight of which have been selected to premiere at the Sundance FIlm Festival. In his latest film, premiering at Sundance this weekend, Rosenblatt shares a story of his own: interviewing dozens of people who were present together at P.S. 194 in New York City, when a group of fifth graders bullied another fifth grader in the yard outside of the school in 1965.

Rosenblatt was one of the bullies.

In an encounter where he recognizes forces outside of the control, Rosenblatt found himself in the presence of one of his fifth grade classmates, more than thirty years after they were in school together and after the therapist-turned-filmmaker changed coasts, trading New York for California. He finds meaning in the Albert Einstein quote, “Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous,” establishing that his encounter with a classmate he hired to do some voiceover work for his documentary, The Smell of Ants, was not chance.

Together, Rosenblatt and his friend began to discuss the moment when a child in their class named Dick was beaten by the class outside. Dick had caused the whole class to be held inside longer because he had broken the rules of their strict teacher, and she punished all of them. Years later, Rosenblatt reflects on that day, and the conversations he had with his classmates fifty years later that ended up in the film. He’s still processing the events that made him part of the bullying, things like the loss of his younger brother and his parents’ lack of involvement. What would he say back to that younger version of himself, knowing what he knows now?

“I think my letter to myself would be to try to forgive myself. I was going through a lot of things, and I think unconsciously that was operating,” Rosenblatt mused. “I think I would say that I have regrets that I didn’t stand up, that I didn’t say stop, that I went along with the group. I had a realization – a line that I cut out from the finished film- that I don’t see a big difference anymore between enablers and bullies. Complicity creates power for them because on their own bullies are not that powerful. I had a hierarchy of culpability for awhile, thinking that because I wasn’t the lead instigator, I wasn’t culpable.”

Rosenblatt says that his parents didn’t really know what was going on with me, that they were clueless to what was happening. He doesn’t blame them because he knows for two years, their focus was on his sick brother. But they weren’t prepared, or educated, to pay attention to their son and his struggle. “They weren’t trained to listen or nurture in a certain way. My dad was not a model of sensitivity. He was very shut down, especially after my brother died, he went into a depression. He was kind of a bully in his own way. He used to say that you have to defend yourself, that kind of thing, old school. He kept a lot of things very within himself.”

The inner angst was going to find a way out. For too many of us, that hurt becomes the fire that we hurt others with. But bullying and complicity are hot topics these days since the assault on The Capitol. While Rosenblatt has been working on this film for the last four years, he says that the recent events have proven how timely and timeless the topic is. “One of my goals is to engage the audience that invites them to think about their own pasts, their own wounds. Several people have seen it and felt like they needed to tell me their story. That makes me feel like I accomplished one of my goals.”

The inner angst was going to find a way out. For too many of us, that hurt becomes the fire that we hurt others with. But bullying and complicity are hot topics these days since the assault on The Capitol. While Rosenblatt has been working on this film for the last four years, he says that the recent events have proven how timely and timeless the topic is. “One of my goals is to engage the audience that invites them to think about their own pasts, their own wounds. Several people have seen it and felt like they needed to tell me their story. That makes me feel like I accomplished one of my goals.”

Investigating the story, Rosenblatt interviewed his fifth grade classmates, with the exception of a few who had passed away and the child they’d bullied. He also interviewed his teacher, who was now in her nineties, and bore a hurt of her own. Some of his classmates saw her as their favorite teacher; others felt they had been treated unfairly. The one-time counselor shared directly, “She’s a project of her time. Her loss [of a daughter] also colors her responses. At the same time, if you watched the film carefully, she kind of started the whole process of this incident, because she employed collective punishment. She kind of set it up because someone had yelled out and couldn’t control himself. She made us all pay the price. He was already picked on but this actual incident was triggered by the way she treated the situation.”

While Rosenblatt’s documentaries aren’t always interviews, usually relying on found footage and voiceovers, he found himself sitting back in silence, and letting people speak out of their anxiety. One of the things the teacher says is that boys who can throw a ball or catch a ball are accepted, and those who can’t are not. “I think there is an interface between sports and acceptance,” Rosenblatt admitted. “Sports brings out emotion, competitive nature. I think it depends on who the coaches are and what the attitude toward winning is. Growing up, I was very competitive, but we had this saying, ‘it’s not whether you win or lose but how you play the game.’ I thought we internalized that.”

“It’s my teacher who brought up throwing and catching. [Those boys who couldn’t] were shamed. The journalist [who came across Rosenblatt’s story and wrote a feature] found my teacher, found Dick. I was taken by how into the story he was, and how personal it was. I was happy to have him talk about being bullied because he’s like a stand in for Dick, smart and well spoken but bullied all the time, death by a thousand cuts. Having that voice was important to me.”

Now, Rosenblatt has lived on the West Coast for thirty years, but he says that you can’t take New York out of a person. He says he has a kinship with the East Coast culture, even if the West Coast energy suits his spirit better. “I like the West Coast, the day to day energy and vibe. It fits better than the dog eat dog, competitive one-upping that happens in NY. There’s that focus on money, on status. I like visiting NY, and happy to be from there, but I don’t miss living there.

This is a real New York story.”

The director is bringing that story to Sundance’s audience, even if it’s virtual and hard to know how people are receiving it. He misses the live audience, the immediate knowledge that his films have moved someone, because of the applause, laughter, or gasp of surprise.

“Besides the people I get to talk to directly, it’s hard to know what the response is. Obviously, I’d love for it to take off and people to spread the word. If in Park City, if I’m a lucky, maybe only a hundred see it. It’s an honor to be at Sundance. With the virtual screening, it’s available for a low price – $25 for all of the non-feature films, and no limit on tickets. It could be seen by thousands of people. I hope it has an impact.”

Jay Rosenblatt has told a story so many people can relate to, taking us on a journey toward healing and accountability. It’s a New York story, but it’s the story of all of us, victims, bullies, and enablers.

Hopefully, everyone will learn to accept each other and one day we can stop saying, “We were bullies.”

Access the film at https://fpg.festival.sundance.org/film-info/5fd15bc004818b1c93648d9a.