By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

As a nine year old, Brian Ivie filmed stories with his friends, echoing the tales spun by J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, and Ian Fleming. While his friends re-enacted parts, Ivie used southern California’s idyllic summers to capture ideas on film, the only activity that held his attention when school and other activities failed through high school. But while the younger Ivie didn’t know that filmmaking could actually be a career, the stories he tells prove that this is certainly his call.

Enrolling in the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, Ivie worked to hone his craft, unaware that one day over breakfast, his heart would take him on a trip across the ocean to South Korea. An article about Pastor Lee Jong Rak and his church’s ministry to save abandoned babies caught Ivie off guard. Initially, he intended to make a short film about this pastor and these children, even though Ivie spoke no Korean and needed a friend to spend hours in Ivie’s USC dorm room editing the raw footage that would become The Drop Box. But Rak’s story of service and faith in the midst of the darkness resonated with Ivie, and he discovered faith of his own.

Comparing his story to that of William Wilberforce, in tone if not extent, Ivie says that he saw how perfect his life was and how troubled these babies’ lives could have been without Rak. Ivie, who is Japanese-American, saw that he had the platform as a film student to bring awareness to the situation. As an aspiring student, hoping for a spot at Sundance, he realized that he was blowing the power to his dorm for a reason – he could show people that he heard and saw them, in even in the midst of tragic situations.

Comparing his story to that of William Wilberforce, in tone if not extent, Ivie says that he saw how perfect his life was and how troubled these babies’ lives could have been without Rak. Ivie, who is Japanese-American, saw that he had the platform as a film student to bring awareness to the situation. As an aspiring student, hoping for a spot at Sundance, he realized that he was blowing the power to his dorm for a reason – he could show people that he heard and saw them, in even in the midst of tragic situations.

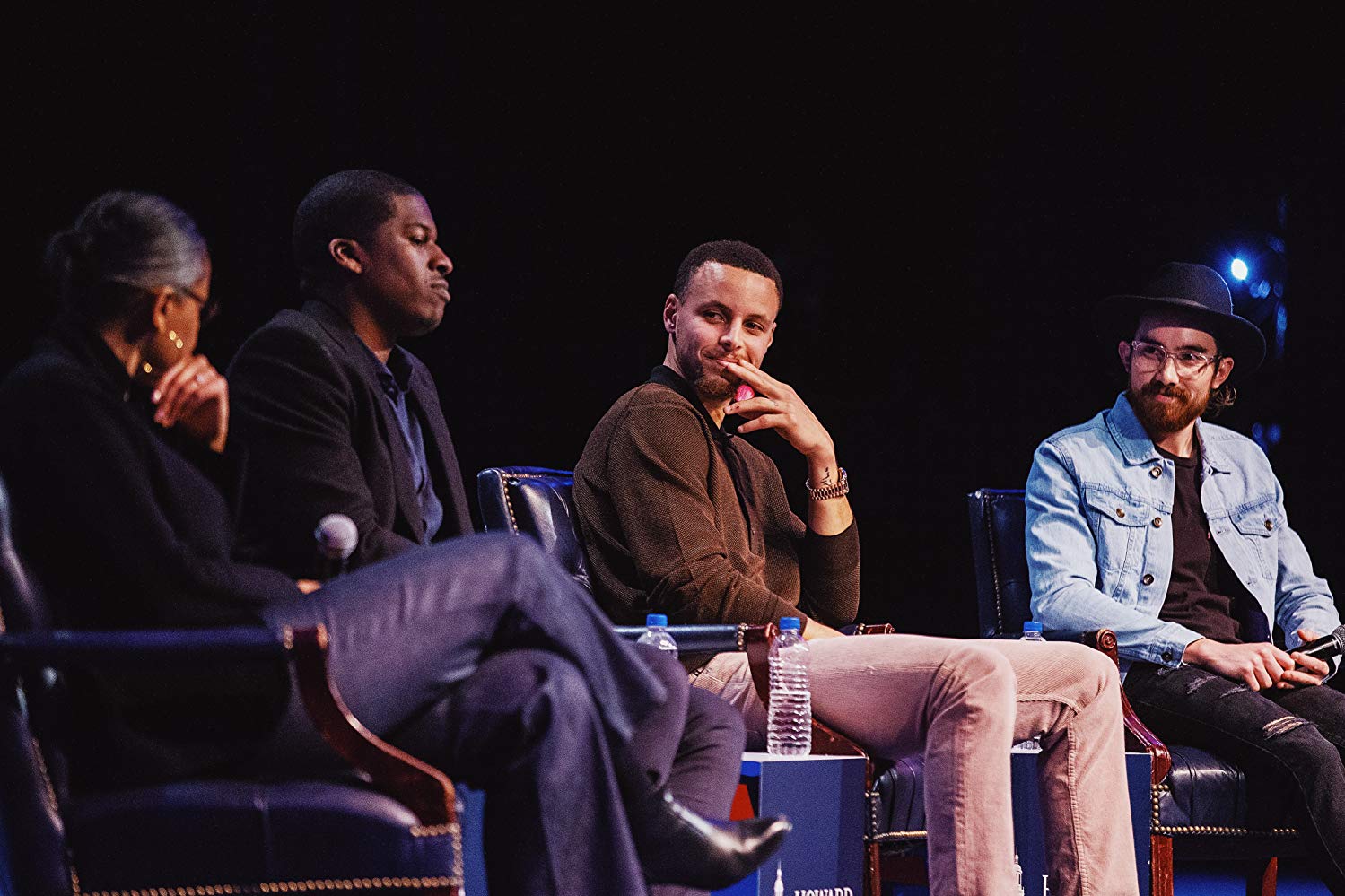

In directing his sophomore endeavor, produced by NBA superstar Steph Curry and Oscar-winning actress Viola Davis, Ivie is still trying to tell the truth, even if it’s offensive to some. This time he’s tackling the murder of nine African Americans in a Charleston (S.C.) church Bible study by Dylann Roof, a white supremacist. Watching footage of the interviews and news reports about the shooting while on his honeymoon, Ivie felt drawn to the story but gave it a year before he pursued it. Then he went to the memorial service, and found himself asking if he should even make a movie about it as he walked through the doors of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

“I wasn’t sure if it was fair to put the families through it after having had to live it already,” admitted Ivie. “We asked if the family even wanted it to happen because you could see that the church had been the one place an African American could feel safe. Maybe I was just supposed to pray and mourn with them? But they said it was what they wanted to do – and they’ve given their blessing on the final version, too.”

“I wasn’t sure if it was fair to put the families through it after having had to live it already,” admitted Ivie. “We asked if the family even wanted it to happen because you could see that the church had been the one place an African American could feel safe. Maybe I was just supposed to pray and mourn with them? But they said it was what they wanted to do – and they’ve given their blessing on the final version, too.”

Filming a documentary in South Carolina was like a graduate course in human, American experience, Ivie says, because he didn’t come to the story with any racial baggage. Yes, his grandmother was interned in a camp during World War II, but he was coming face-to-face with the troubling brokenness of the black and white segregation of the American South still present years after the civil rights movement.

“One of the AME pastors calls Charleston ‘the Confederate Disneyland,’” explained Ivie. “It’s a sad, broken racial history, but it’s also truth that there’s something charming about the South. That’s what makes it even more startling. I came face-to-face with what’s broken, and found myself asking, ‘How do churches respond to this? What was it like to make the decision to tell African Americans they had to sit in the balcony or only come through certain doors?’”

“It’s disturbing but light always shines brightest in the dark. These black churches have been burned, but they kept rising up again.”

“We see a lot of shootings and it’s hard to keep track of them all,” the director shared. “When you’re aware of the issue, you see it everywhere: the church, the mosque, the synagogue. The killer had gone to a church like the one I go to, and this made it personal, like if someone walked into a high school and did this, and all of the students then rise up.”

“We see a lot of shootings and it’s hard to keep track of them all,” the director shared. “When you’re aware of the issue, you see it everywhere: the church, the mosque, the synagogue. The killer had gone to a church like the one I go to, and this made it personal, like if someone walked into a high school and did this, and all of the students then rise up.”

Ivie thinks repentance is necessary because of the wounds that are still there in the systemic racism of some areas. But he sees that forgiveness and grace are also necessary, that redemption is possible if the two sides can meet each other. “There has to be a real desire for justice and forgiveness, not faux forgiveness,” he proposed. “What are we willing to give up to move us forward?”

Emanuel isn’t just a movie that sits patiently waiting to be observed and then walked away from, but it captures a moment in time and then asks the audience to participate in change. Putting his own money and other producers’ money behind the film, along with investors, Ivie explained that every dollar the producers make from the film will go to the families who lost loved ones in that Bible study, certainly the darkest day in Emanuel’s 203 year history. Even in their pain, he says it’s incredibly clear how the faiths of the family members impacted the Roof trial and the witness that the deceased church members leave behind.

“Forty-eight hours after the shooting, some of the families decided to give the killer their forgiveness. One man stood up in court after losing his wife and said, ‘I forgive you. Give your life to Christ. You’ll be better off than where you are now,’” shared Ivie.

While The Drop Box had given Ivie the opportunity to observe pain and its impact on people, he wasn’t a Christian when he started filming. “I like to say that Drop Box was God’s way of introducing himself to me, and Emanuel is my way of introducing God to other people.”

The director doesn’t want people to think there are any cutely packaged answers in the documentary, avoiding the glossing over of the more difficult moments or hard-to-swallow facts. “A lot of Christian cinema tends to avoid going through the process of pain, as if as soon as you get saved, everything is just perfect. But that’s not Jesus’ experience or Peter’s experience or so many of the other early church leaders,” Ivie said. “Emanuel showed me it’s okay to stand in the in-between and grey of life, because of the extraordinary faith of the people there, to love their enemy, despite of what he did to them.”

“It’s counter-cultural. I just wanted to tell their story, and stay out of the way.”

On June 17 and June 19, the anniversary of the shooting and of the courtroom forgiveness, audiences can attend screenings in nine hundred theaters nationwide. For more details, visit emanuelmovie.com.