By Jacob Sahms

A few weeks ago, Mike Friedrich stood in front of a small group gathered for a retreat. As an ordained deacon in the United Methodist Church, Friedrich’s leadership in the five-day retreat on “Ordinary People with Extraordinary People” was unsurprising. But what all of the participants didn’t know was, that at one time, Friedrich had written stories about Batman, Iron Man, and others, published on the colored pages of superhero powerhouses like Marvel and DC.

That was then, and this is now.

Last month, Friedrich, the emerging ministries specialist for the Bay District of the California-Nevada Conference of the UMC, was recognized at Comic-Con International with the Bill Finger Award for Excellence in Comic Book Writing. Friedrich’s work, on DC properties like Justice League of America, Batman, The Flash, Green Lantern, Teen Titans, and The Phantom Stranger, and later on Marvel’s Iron Man, Ant-Man, and Captain Marvel, all began when he started writing to Julius Scwhartz, for those notes to the editor that once filled the back pages of every comic book. His love began in his upstairs attic, unpacking the stories of some of his favorite characters when he was just twelve years old.

“My parents loved babies,” the seventy-year-old remembers. “I’m the oldest of nine so they had doted on me as a kid but by the time I was ten, there were more babies. So I retreated up to my attic room, escaping in one sense but experiencing something deeper.”

An avid collector of Batman comics, the adolescent Friedrich believed that the world should be fair, and as he got older, he discovered that it wasn’t. Initially, he didn’t set out to be a comic writer but he wanted to express himself, and began replying to the stories he read with letters to the editor. Slowly at first, with simple likes or dislikes of elements of the stories, Friedrich’s writing built to liking certain elements, then pointing out slight improvements, and finally proposing what he would write if given the opportunity.

“I received the answer, ‘sure, give it a whirl!’” the deacon shared. “The editor I wrote to had lost two main writers in the last year, one to retirement and one had just lost his stuff. No one was getting into writing comics and so many people were leaving, that he was open to a fan writer trying out stories. Today, you need a TV credit to write in comics, but they were so desperate in the 1960s that there was this upswing of all these kids.”

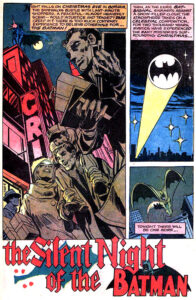

That influx of young comic writers led Friedrich to New York City, where he began writing for DC. [His favorite story is “Silent Night of the Batman” from 1969 (Batman issue 219).] By 1972, he was a Marvel comic writer, covering the majority of Iron Man’s stories from July 1972 to December 1975. For ninety days in the summer of 1972, he was the roommate of Jim Starlin, who pitched the idea for Thanos and Drax the Destroyer (now, of the Guardians of the Galaxy). Co-scripting the initial issue of Thanos’ existence netted Friedrich a credit in the evil megalomaniac’s creation – and the occasional royalty check, especially now that Marvel’s cinematic universe has run the full narrative of the villain through Avengers: Endgame.

That influx of young comic writers led Friedrich to New York City, where he began writing for DC. [His favorite story is “Silent Night of the Batman” from 1969 (Batman issue 219).] By 1972, he was a Marvel comic writer, covering the majority of Iron Man’s stories from July 1972 to December 1975. For ninety days in the summer of 1972, he was the roommate of Jim Starlin, who pitched the idea for Thanos and Drax the Destroyer (now, of the Guardians of the Galaxy). Co-scripting the initial issue of Thanos’ existence netted Friedrich a credit in the evil megalomaniac’s creation – and the occasional royalty check, especially now that Marvel’s cinematic universe has run the full narrative of the villain through Avengers: Endgame.

“All I did was put in three days of regular comic work, just like any other work I normally did,” the self-effacing writer-turned-minister shared. “It’s a mystery to me, until five or six years ago, comics were just something I wrote fifty years ago.”

As a comic writer, Friedrich says he worked to convey as much meaning as possible, but as a pastor, there’s layer after layer of meaning meant to be conveyed through a sermon. “Sometimes, I just want to say, ‘Love God, love your neighbor, let’s go home!’” he shared with a chuckle. But even ending up a minister is still something of a mystery to him after experiencing a call to ministry in his sixties.

The exploration into his own calling, and in how theology and culture could work to share the gospel, led Friedrich out of his home into the church down the street, which he says just happened to be Methodist. Hungering for more, he took classes, looking for the ways that people built community in the secular world, like at football games or rock concerts, instead of the way they once had in church. He says his own connections led him into a Methodist ordination service for a friend of his, where he heard Mark Miller’s rendition of “O For a Thousand Tongues,” and knew he needed to be part of something bigger. So, he started taking classes, and gradually found himself pulled deeper into another calling.

Friedrich’s favorite class at the Pacific School of Religion was titled Pop Goes Religion, exploring the intersection of pop culture and theology. His professor most likely taught oblivious to the fact that a real conveyor of comic culture sat in the lecture hall just like the students fresh out of college. “Theology operates in pop culture, and organized religion tends to miss the connection,” proposed Friedrich. “Often, it denounces pop culture and tries to be countercultural or it tries to appropriate it, but it rarely dialogues. But John Wesley understood it, and he recognized that the Holy Spirit could be reached through music so he wrote his hymns to the beats of drinking songs. The rhythm reaches past our conscious level to a deeper spiritual level.”

“We’re challenged to stay connected to our people and our culture. The rituals we still go through that have no collective meaning, they fall away because people don’t want to come back to those. The trick is to discern in pop culture what leads to light and what leads to darkness. It’s not immediately obvious.”

“We’re challenged to stay connected to our people and our culture. The rituals we still go through that have no collective meaning, they fall away because people don’t want to come back to those. The trick is to discern in pop culture what leads to light and what leads to darkness. It’s not immediately obvious.”

Just like his hero Batman recognized that there was a line that separated the light from the darkness, where he would walk into the shadows to fight evil but choose not to kill, Friedrich says the role of pastor is to make the discernment between the light and the darkness public. As a deacon, he preaches less, and works out in the world more – finding places where the church can exist in new locales, like a church he’s working with that it’s in an apartment building or petitioning for Palestinian human rights. He says, unironically, that he’s “semi-retired.”

But the questions he asked in the attic as a twelve-year-old still drive him. Why do these stories, from the pages of DC or Marvel, or the narrative of the Bible, matter? He finds himself looking at the world we live in, and seeing that people feel powerless, that there are forces so large that they can’t handle them – and then there are these creative, major players who control their worlds by using their powers for good. You could be talking about the worlds of comic book characters … or stories from the Bible.

“Our spiritual connection gives us access to the power of the divine,” Friedrich the minister says. “We wouldn’t have that on our own. But most people aren’t even taught in Sunday School to feel that way. Superheroes provide ready access to that kind of connection, that if you’re willing to sacrifice yourself, you can change the world and evil won’t triumph.”

“I’ve felt that way my whole life. I’m still exploring that, every time I see an Avengers movie!”

Mike Friedrich, mythology creator and real-world pastor. That’s quite the byline.