By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

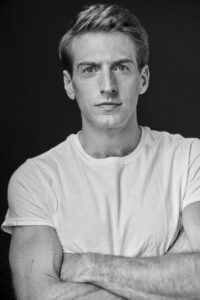

Fran Kranz, best known for his roles in FOX’s Dollhouse and the thriller/horror film The Cabin in the Woods, shows a depth of thought in his directorial debut that proves actors play roles and screenwriters tell stories. Unlike the fanciful work Kranz has acted in, his story Mass tells about an all-too-realistic situation: the conversation between two sets of parents after a school shooting. This isn’t the first film about a school shooter, with Beautiful Boy, We Need to Talk About Kevin, and I’m Not Unashamed releasing over the last decade, but sitting with Kranz and one of his four stars to discuss the movie, it’s abundantly clear that this is a different angle.

Reed Birney, Ann Dowd, Jason Isaacs, and Martha Plimpton star in a film that largely takes place in real time in the basement of a small church. The two sets of parents, one of a victim and one of the killer, have been set up to meet by an outside broker, and once they assemble in the room, around a simple table, the audience is locked into their discussion without interruption until they’ve exhausted what they have to say. As Kranz is responsible for the script and the direction, the question comes naturally: why did he choose to make this his directorial debut?

Before each question, Kranz stops, reflectively, and then responds. “I was thinking a lot about forgiveness and if I was capable of it. [School shootings] happen a lot in this country and I was a new parent, and I was thinking about what I would do, how I could move forward, if that was even possible if that happened to someone I loved.”

Before each question, Kranz stops, reflectively, and then responds. “I was thinking a lot about forgiveness and if I was capable of it. [School shootings] happen a lot in this country and I was a new parent, and I was thinking about what I would do, how I could move forward, if that was even possible if that happened to someone I loved.”

Twenty years earlier, Kranz read about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that happened in South Africa after apartheid was ended, and watched footage of the interviews. He’s been wrestling with the potential to forgive ever since, asking if he was capable of such grace. “I was blown away. It was so inspiring to read and to watch these amnesty hearings, but I was also deeply troubled and scared by them because I did not think I could participate or forgive someone for taking a loved one so dear to me. So there’s been something inside of me that I’ve needed to work through, or deep down that has stuck with me. My daughter now is five but I started thinking about this when I was one and a half years old. The journey of this film is my working through these ideas and thoughts. It’s emotionally hard, formidable like an endurance test, but that’s because it’s meaningful. I’m desperately trying to figure this out myself.”

Ann Dowd, who plays one of the mothers in the film, looks up at Kranz and asks, “Do you know? Have you figured it out?”

Ann Dowd, who plays one of the mothers in the film, looks up at Kranz and asks, “Do you know? Have you figured it out?”

“I don’t know!” Kranz exclaims, turning to her. “But I do know that what these people do is the most extraordinary thing in the world. I can’t think of anything more admirable, or courageous, or inspiring than sitting across the table from someone you’re at odds with, have hate for, and trying to work through that. I think it should be lifted up and celebrated, and that’s why the movie takes place in real time and we don’t get to leave the room until they do.”

That room, part of the fellowship hall area of the church, isn’t the sanctuary or an office where counseling might take place. But it’s part of the church, and Kranz says there’s nowhere else he could imagine the conversation happening the way it does.

“I was raised Catholic, going to church,” shares the director. “I like church, and I like going when I do go. I believe in the values, themes, and stories of Christianity. It’s a mistake to forget about them because of whatever mistakes or crimes that have happened in the human institution. They need to be kept close. I needed spirituality in this movie because the themes are spiritual.”

“In his book, No Future Without Forgiveness, Desmond Tutu writes, ‘Forgiveness, reconciliation, and reparation are not the currency of political discourse, and they’re far more at home in a religious realm.’ I couldn’t place this in a private home or a community center, although I’d seen examples of them, but I thought something would be lost. People are talking about life, death, and grief, meaning. The movie is about finding meaning, and the characters all have a relationship with the spiritual even if they don’t know it or want it. It was too important for me to not have God or the notion of God close by.”

While Kranz has been wrestling with the material, the spiritual dialogue in himself for years, Dowd says that it’s the writing the director did that allowed the four actors to play the voices who make up the conversation. “It always begins for an actor with the text,” Dowd shares. “If you read something that is beautifully, completely written as Fran’s script, the journey of the character is clear. You trust that, nothing rings as false, so you know you’re in good hands.”

Dowd continues, “We went through the text in two days, the four of us, creating an awareness consciously or unconsciously that we needed to trust each other with everything and know that we were safe. So when we went home and went our separate ways, that when we came back three weeks later in shooting in Idaho. You want to keep it very simple; I don’t think of big things. It’s my job to consider what it landed. What was her life? What is her life? I imagine she’s the peacekeeper in the family. ‘Your dad didn’t mean it that way, honey. He didn’t mean to be so stern so don’t take it so personally when he does that. Just come to me.’ And saying to her husband, ‘You can’t speak to him that way. It just shuts him down.’ Just trying to keep everyone in some level of harmony and believing that’s possible. All of that is destroyed [with the shooting].”

“The warrior in her steps aside because there is no … everything that we think as human beings that we need to get through life is gone, gone. The remarkable thing about her is that she doesn’t try to build them again. Those words don’t describe the reality of their lives now. [Quoting her character] ‘I don’t expect you to forgive. How could you?’ She becomes a listener. I’ll never let go of that woman because she teaches me and taught me in that room.”

The process of making the movie taught Kranz, too. It’s emboldened him to work for the future he wants for his daughter, and for a world that’s more loving, more forgiving, more compassionate.

“What these people do takes such courage but I don’t want it to be extraordinary,” explains Kranz. “We live in this divided country, and I worry a lot about the world that my daughter will grow up into. If we can’t repair these broken relationships, then I don’t know what the future looks like. I want to see this kind of conversation, this honest conversation where there’s full disclosure on one side and decency from the other, respect from the other. The intention only to heal, forgive, or reconcile and not to be punitive or want retribution. The circumstances of the film are large and the hardest that you could imagine. But I want to find the ways that I can behave that way in my own life, with smaller things, in relationship to child, wife, father, brother, friend. I want to find the ways to act like this more often for myself, and that’s why I presented it simply, unadorned.”

“I don’t know if I’m always capable of it, but I want to make forgiveness ordinary.”

Mass debuts in theaters on October 8.