By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

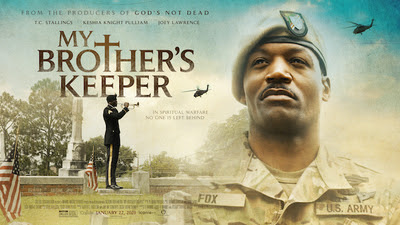

In My Brother’s Keeper, Army sergeant Travis Fox (TC Stallings) returns home from his sixth deployment after his best friend, Ron “Preach” Pearcy (Joey Lawrence) and his entire Ranger platoon are killed in an explosion. Working to settle his deceased parents’ affairs, his battle with PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) rises up to confront him at home, before he seeks support from a church counselor (Keshia Knight-Pulliam), who helps him rediscover his faith. While the film, out in January 2021, is fictional, it has its roots in the childhood and twenty-four years of service of screenwriter Ty Manns, who understands all too well what PTSD can do to a person and their family. This is part one of our two-part conversation with Manns.

Manns grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in coal mining country in West Virginia. As a child, he says that he didn’t have much to look forward to even though his childhood was filled by his loving parents, friend, and a close-knit neighborhood. Even then, he was dreaming about getting away and what stories he would tell to do so, years before he joined the Army.

“Dirt roads and outhouses were part of everyday living. I always had these creative desires, this creative nature about me. My favorite comic book was Conan the Barbarian comic books. My dad would buy them for me all the time, and I would bubble out those stories on my own sheets of paper,” he remembers. “The military was my escape from small-town West Virginia. Every young adult I grew up with back in the day went into one of the four branches, to get out of that small environment.”

Intent on spending four years in the military to get out of West Virginia and make enough money to go to college, Manns enlisted. But then one day he woke up and realized how much he loved serving his country, and being in the Army, so he transitioned from enlisted to officer by way of two years of college. He says he wanted the hardest job in the world – leading infantry soldiers as an officer – even while he was business communication, putting his love for film and creative writing on the back burner. When it came time to transition from the Army to filmmaking twenty-four years later, he says it was easy, because he’d just been postponing that opportunity, and had never really stopped learning how to write or how to be a filmmaker, soaking up every lesson he could along the way.

Intent on spending four years in the military to get out of West Virginia and make enough money to go to college, Manns enlisted. But then one day he woke up and realized how much he loved serving his country, and being in the Army, so he transitioned from enlisted to officer by way of two years of college. He says he wanted the hardest job in the world – leading infantry soldiers as an officer – even while he was business communication, putting his love for film and creative writing on the back burner. When it came time to transition from the Army to filmmaking twenty-four years later, he says it was easy, because he’d just been postponing that opportunity, and had never really stopped learning how to write or how to be a filmmaker, soaking up every lesson he could along the way.

Still, the story Manns has to tell in My Brother’s Keeper faithfully combines three of his loves: the Army, storytelling, and God. Committed to telling people how much God loves them, the screenwriter sees film as the way he can best do that now, even as he watches what happens to minority communities, women, and people in the military today. “It’s frustrating at times, but more than anything it’s painful because it leads me back to the men and women who served under me who aren’t with us today. They gave their lives in sacrifice on a mission or who came back and didn’t get the attention they needed, and committed suicide.”

Now, with two sons in the service, one a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps and one in Army ROTC aimed at being a second lieutenant next summer, Manns reflects on all of the opportunities that the military has to offer, and still sees the threat to his children as young black officers. Still, his film and his faith reflect this core belief – that we as a nation are better than we’re showing right now.

“I believe we’re a better nation of people – we will be better than what we are now. What we are now is my perception, I believe we will be a better nation than what we’re experiencing right now, in treatment of people, a leader who appears to speak out against our military,” Manns proposes. “I believe we’ll see a change in that rhetoric because I don’t believe that rhetoric is necessary. This thing about race, and the complexion of our skin, is ridiculous. When you serve in uniform, you gain a quick appreciation that it’s not the person’s complexion lined up next to you but their dignity and drive.”

“I believe we’re a better nation of people – we will be better than what we are now. What we are now is my perception, I believe we will be a better nation than what we’re experiencing right now, in treatment of people, a leader who appears to speak out against our military,” Manns proposes. “I believe we’ll see a change in that rhetoric because I don’t believe that rhetoric is necessary. This thing about race, and the complexion of our skin, is ridiculous. When you serve in uniform, you gain a quick appreciation that it’s not the person’s complexion lined up next to you but their dignity and drive.”

“I’m thankful to God for every second of my time, for every second my boys will experience, that they’ll learn what we couldn’t teach them growing up in small town Alabama. They get to go off to different countries, meet other people from small towns and big cities, and see that the problem we have is evil rhetoric of hate, that people inside just want to get along with each other, to judge you on your merits, not what’s said about you.”

“We’re challenged in moments in time and we’re facing a challenge. I don’t give up hope.”

The screenwriter doesn’t suffer from PTSD but he does suffer. As a disabled vet, Manns says that the majority of his disability is mental illness based on pain connected to the seven broken bones, and five surgeries, he’s undergone. Now, he’s supposed to take forty-two (42!) pills a day to manage his pain, but he can’t if he wants to communicate coherently through interviews like this one. And yet, he sees himself as blessed, with a story to tell.

“I’ve been blessed. I’ve witnessed PTSD through my father who was a Vietnam vet who has passed now. It drove him and my mother to a point, where after a massive outburst he held a knife to her head, and she was going to divorce him. My grandmother suggested they go to visit the pastor for counseling because they couldn’t afford any other counseling.”

The end result of the counseling was that Manns’ father became a pastor, and the family saw the change in him (and their family) as he grew deeper and deeper in his faith. Manns says that the church saved his family, and his dad’s life, as well as providing salvation from the “PTSD demon.” When Manns went to serve himself, he focused on being mentally prepared for what he would face, and while he doubts there’s medical evidence for that impact, he knows that watching his dad fight through it helped him be ready. And yet, the scars are remain, as Manns gets emotional talking about his fallen comrades.

Stay tuned next week for the second part of the interview.