By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

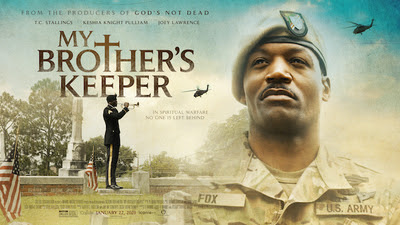

In My Brother’s Keeper, Army sergeant Travis Fox (TC Stallings) returns home from his sixth deployment after his best friend, Ron “Preach” Pearcy (Joey Lawrence) and his entire Ranger platoon are killed in an explosion. Working to settle his deceased parents’ affairs, his battle with PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) rises up to confront him at home, before he seeks support from a church counselor (Keshia Knight-Pulliam), who helps him rediscover his faith. While the film, out in January 2021, is fictional, it has its roots in the childhood and twenty-four years of service of screenwriter Ty Manns, who understands all too well what PTSD can do to a person and their family. This is part two of our two-part conversation with Manns.

The end result of the counseling was that Manns’ father became a pastor, and the family saw the change in him (and their family) as he grew deeper and deeper in his faith. Manns says that the church saved his family, and his dad’s life, as well as providing salvation from the “PTSD demon.” When Manns went to serve himself, he focused on being mentally prepared for what he would face, and while he doubts there’s medical evidence for that impact, he knows that watching his dad fight through it helped him be ready. And yet, the scars are remain, as Manns gets emotional talking about his fallen comrades.

“I lost two soldiers who served under me to PTSD who committed suicide. That’s a hard pill to swallow. They were great young men, who did their jobs, and when they returned they didn’t get the care they were begging for. I remember talking with one of them shortly before he committed suicide, and telling him to call me any time, day or night, but the demon was bigger than me or my advice,” shares a passionate Manns.

“I wanted to write a story that wasn’t an indictment on anyone. I didn’t want it to be an indictment of the military. You hear these football players talking about ‘I know what I’m doing, getting concussions, making millions.’ The military men and women are very smart and know what we’re putting ourselves in front of.’

Manns says that if you suffer from PTSD, whether it’s military service-related, first responder, or something else, that if you can’t get the support you need through the medical field, that there’s a church door that will open up for you. He says that those suffering should admit they need help, that they need someone to talk to, and while it might be the pastor, or a deacon, or the member of a prayer team, whoever is willing to listen will be the one God uses to help them make it to the next day.

Manns says that if you suffer from PTSD, whether it’s military service-related, first responder, or something else, that if you can’t get the support you need through the medical field, that there’s a church door that will open up for you. He says that those suffering should admit they need help, that they need someone to talk to, and while it might be the pastor, or a deacon, or the member of a prayer team, whoever is willing to listen will be the one God uses to help them make it to the next day.

So how might someone help? What should they do? Manns explains that you don’t have to be trained or even super experienced to make a difference, but you need to identify your own fear of inadequacy.

“I would say that you’re not inadequate, because everyone, especially a person of faith, can listen,” he proposes. “That’s all these folks who are suffering want to do most of the time, is talk to someone. If you can sit and listen, you’re not inadequate. Fear makes us think we don’t know enough, ‘I’m afraid because I didn’t serve,’ but you need to understand that the person with PTSD is trying to escape a dread of their own. Sit and listen. Believe me, listening to someone suffering from PTSD or mental illness is a huge relief for that person.”

The movie itself takes Manns back to his own childhood, to the fits of PTSD rage that his father exhibited, that moved his mother to tears as he showed her. He remembers though the way that his father overcame the feelings of dread, the outbursts of anger, and the way the church showed him the means to overcome. He shares one final memory of the man who modeled service, and love, and faith to him, that explains who proud veteran, father, and man of faith Ty Manns is today – and what his movie aims to show the world.

“I remember him getting off of a bus in small-town West Virginia, during the Vietnam War. The protestors are spitting and throwing things at the soldiers, but he found us in the crowd, and kept walking toward us. This woman came running up and came dangerously close to us, to yell and scream at him. He said, ‘You can do whatever you want to me but don’t touch my family.’”

“I remember him getting off of a bus in small-town West Virginia, during the Vietnam War. The protestors are spitting and throwing things at the soldiers, but he found us in the crowd, and kept walking toward us. This woman came running up and came dangerously close to us, to yell and scream at him. He said, ‘You can do whatever you want to me but don’t touch my family.’”

“When we got home, he sat us down and said, ‘Never hate or dislike because someone has something to say.’ I was like, ‘No, I hate her, she was calling you the N-word! How can you say that?’ But he taught us not to hate, to be young men who cared about everyone, to never let race or economic status or anything else get in the way of being a good person.”

“Now, I understand. And I pray I’ve been able to pass that down to my sons.”

My Brother’s Keeper is in theaters January 2021.