By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

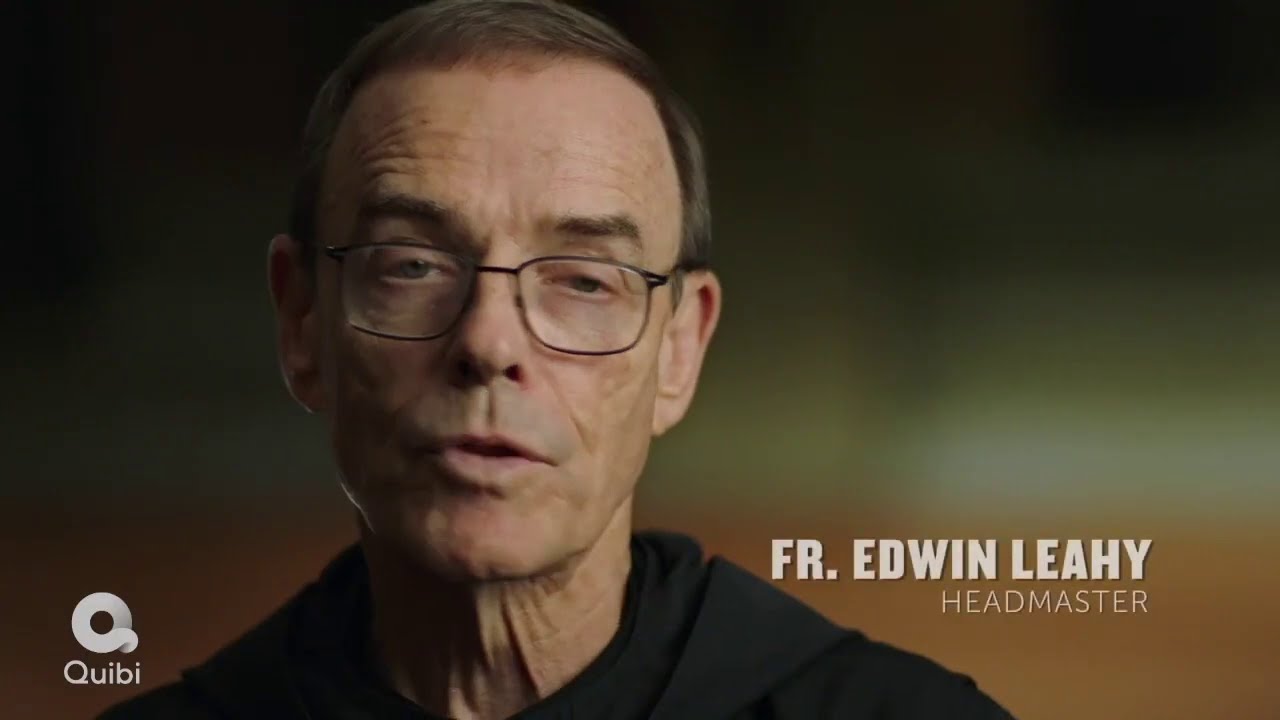

Watching Quibi’s Benedict Men, produced and narrated by Steph Curry, there are basketball players, who fly up and down the screen via Quibi’s documentary series. Their stories move quickly, struggling on and off the court to balance school, the game they see as a way out, and the relationships around them. And yet, in the middle of the sound and the fury stands a calm, intellectual priest, Father Ed Leahy.

Leahy, who graduated from St. Benedict’s Prep in 1963, had an interest in the monastery, and after pursuing his education, he professed first vows in 1966, solemn vows in 1969, and began working at his alma mater as a coach and teacher. Then, in the effects of unrest and rebellion up the hill from the prep school that began in 1967 caught up with the enrollment, and in 1972, the school closed. A proud heritage of German and Irish immigrants coming to the school since 1868 was suddenly undone.

The school lost fourteen monks to another Abbey with no work available in Newark. Leahy was empowered to see what the city needed and to figure out a way forward. Starting in July 1973, with no intention of reopening an educational venture, Leahy saw how racism had invaded the mindset of the school as they eventually started a school but didn’t call it “St. Benedict’s Prep.” He brings the words of “The Big Book,” Bill Wilson’s manual for Alcoholics Anonymous, to mind: take the cotton out of your ears and stick it in your mouth: “Just be quiet, and accompany people through life. You don’t need to impose your own worldview on theirs but serve them.”

The school lost fourteen monks to another Abbey with no work available in Newark. Leahy was empowered to see what the city needed and to figure out a way forward. Starting in July 1973, with no intention of reopening an educational venture, Leahy saw how racism had invaded the mindset of the school as they eventually started a school but didn’t call it “St. Benedict’s Prep.” He brings the words of “The Big Book,” Bill Wilson’s manual for Alcoholics Anonymous, to mind: take the cotton out of your ears and stick it in your mouth: “Just be quiet, and accompany people through life. You don’t need to impose your own worldview on theirs but serve them.”

He continued, “A father, Carl Lamb, asked in a parents meeting, ‘Why was it good enough to be St Benedict’s Prep when it was all of you and not now when it’s all of us?’ His question reopened St. Benedict’s Prep.”

When they returned as St. Benedict’s Prep, Leahy says they had something most urban schools didn’t: heritage. While schools in cities around the country were filling with people of color, there was no tie to the people who had been in the schools before. Instead, Leahy saw alumni from prior to the closing embrace the younger, black students who came later.

“A guy in a bakery who is eighty years old and graduated in ‘51 walks up to a kid with a St. Benedict’s shirt on and embraces them in conversation.”

This idea builds people up, echoing St. Benedict’s mantra that “what hurts my brother hurts me.” Instead of diminishing people, the school built people up, and taught the students what they were up against historically in society and in church. Leahy says that slavery worked early on by negating the dominant culture of Africans brought to the United States, and then has been maintained by destroying the legacy of the African male, and the African male himself. Of course, building up young black men doesn’t work for everyone.

“There were people in the community and the church who weren’t happy. It wasn’t ugly because we were living in Newark surrounded by black people who embraced and loved us, into a whole other way of living. What looked like a disaster turned into a huge blessing. I was one of the people who was angry and thought, ‘Why would God let this huge disaster happen?’ God knew better.”

The way through disaster, Leahy says, has been all about love. He tells the parable of two Jewish men. One asks, “Do you love me?” The other says yes. The first man asks, “Do you know my suffering?” The other says, no. The first one then asks, “How can you say you love me if you don’t know my suffering?”

“It’s so critical to know someone else’s suffering,” Leahy proposed. “We need to understand the suffering of our brothers and sisters of color. It changes the way you live your life. [St. Benedict’s] has been loved into another way of being. The spontaneity, the ability to paint pictures with words that’s unbelievable, these guys are amazing.”

Statistically, Leahy points out that it’s more likely that graduates of St. Benedict’s will become neurosurgeons than pro basketball players, but the media is controlled by white people who highlight athletes. “They don’t see lawyers or people working in Goldman-Sachs,” he says. “Their world becomes limited. If you’re trapped because you don’t have the money to travel or expand yourself, it’s a disaster.”

But the flipside is the community that they’ve been fostering since 1972, or 1868. And Leahy is willing to provide the daily homily, whether it’s to his students, as part of the documentary, or one-on-one to a reporter. And the message is the same.

“Everybody’s heart’s desire is community. We think about God as community, as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Left to ourselves it’s a lonely existence. Our country and communities are fractured.”

“We need to get ourselves to practice accepting the other the way the other is; [instead] we always want to fix or change the other so we’d like them more. It happens in marriage, the church. Love transforms us. Love is the dimension of the cross. We have to be willing to suffer for the sake of the other. Christ died for us the way we are. I know what I am and He died for me. Then He says, ‘Love the others as I have loved you.’ I have to offer myself for the sake of the other.”

The conversation is ongoing; the headmaster’s next call will be to the Abbot who called during the interview. But whether the calls are to students, parents, reporters, or his ecclesial superior, Leahy carries the message with him. It’s been nurtured for years behind a fence around the St. Benedict’s property. The fence isn’t there to keep priests in or the community out. It’s there to mark the holy ground, the holy work of what happens when young men step onto the campus to learn, to be challenged, to grow, to love.

St. Benedict’s stands as a sign that the world may change around the church and the students may change over time, but the lessons, and the Gospel, remains the same: love one another, by the power of the Holy Spirit.