By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

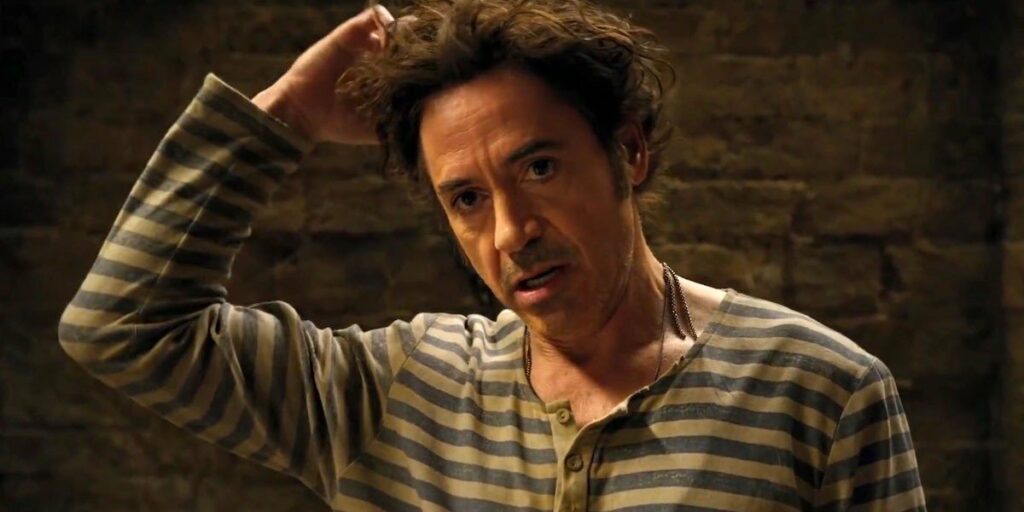

Don’t get me wrong: Robert Downey Jr.’s Dolittle is significantly more entertaining and enjoyable than its 18% score on Rotten Tomatoes would lead you to believe. But the film’s messages, about working with others who are different from you and overcoming the insurmountable wall of grief, provide a substantial pool of issues to reflect on for yourself or discuss with family and friends.

Hugh Lofting’s mid-1900s creation has been adapted into a musical, an animated television show, and a series of Eddie Murphy comedies, but the wealth of opportunity is invested in here thanks to Stephen Gaghan’s writing and direction. Dolittle is holed up in his animal sanctuary having shunned everybody, well, every human body, since the death of his adventurer wife Lily seven years ago. Two unrelated events, the sudden illness of the Queen of England and the accidental shooting of a squirrel, lead to Dolittle’s being drawn out of hiding to save the day.

Rather than review the film (click here for Peyton’s take), I’ll look at the way that Dolittle echoes last year’s Wonder Park in exploring how we overcome our heartbreak. While June Bailey is just a kid in the animated feature, she and Dolittle share the human response to grief: they pull away from relationships and become reclusive in their interaction. In both films, they are reminded that they need people because we’re relational, communal, by nature, and that there’s a responsibility they have to serve others to find their true selves.

Rather than review the film (click here for Peyton’s take), I’ll look at the way that Dolittle echoes last year’s Wonder Park in exploring how we overcome our heartbreak. While June Bailey is just a kid in the animated feature, she and Dolittle share the human response to grief: they pull away from relationships and become reclusive in their interaction. In both films, they are reminded that they need people because we’re relational, communal, by nature, and that there’s a responsibility they have to serve others to find their true selves.

While both of the movies I’ve mentioned are kids films, unlike the 1998 Robin Williams-driven film Patch Adams, there’s more going here than the superficial “quest” film to find the cure for Queen. In the midst of all of the goofy shenanigans is a character arc for Downey’s Dolittle that’s greater than any transition for him in a Marvel movie: we see that he will still miss his wife, still mourn her absence, but he will return stronger as an individual because she helped him explore his true self and follow his true love– serving both humans and animals through healing. While tragedy threatened his happiness and made him want to curl up in a ball of fetal grief, his journey to the Eden tree (seriously, a tree that provides healing and potentially eternal life to those who experience its fruit) is one of awakening out of the fog of grief.

For those in the midst of grief, and those around them praying for their healing, Dolittle reminds us of the ways that our community helps determine who we become when we’re experiencing success and who we will be after we have traveled through a low place (loss of a loved one, losing a job, experiencing depression or a dark night of the soul). Dolittle’s friends both old and new have much to do with his healing, and it’s in that journey that he discovers (again) who he was always meant to be.

We should be reminded of our need to not recoil, to not give up hope, but to really live as a testament to love. We should be moved to proceed forward, in stops and starts, imperfectly, recognizing that there’s beauty on the other side of what we’ve experienced. It won’t be full of talking animals and mythic quests, but it still requires us to be courageous in the face of what we’ve seen.