By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

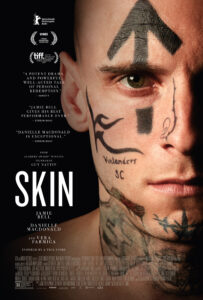

In 1991, fourteen-year-old Bryon Widner lived homeless until the night he attended a punk rock show and fell in with Nazi skinheads who gave him cigarettes and a place to call home. Over the next sixteen years he would cover himself from head to toe in tattoos, developing relationships within groups of white supremacists and finally founding one of his own, the Vinlanders Social Club. But after meeting a young woman and her children, Widner decided it was time to leave the VSC – jumping out of a gang whose brutal violence he had helped initiate. It was going to take help from an unlikely source for Widner to succeed, and in Guy Nattiv’s spellbinding story Skin, audiences nationwide will see the power of a cross-cultural intervention in a gritty, personal way.

While a 2011 documentary, Erasing Hate, captured the visual transformation that Widner went through, more than two dozen painful laser treatments to remove facial tattoos on his face and neck, he is clear that the visible scars were much easier to remove than the emotional ones.

“I was longing for something familial, and that’s what the Neo-Nazis offered me,” Widner shared. “This was before the Internet, before much of anything really, and we didn’t know what a Neo-Nazi was. Honestly, I would’ve joined whatever group got to me first.”

Widner saw firsthand how the groups like the VSC offered safety, protection, and the sense of family to impressionable youth who no one else is listening to, or at least who feel ignored. He says that those are the things he used to offer when he moved from initiate to recruiter, the way that even in the twenty-first century, hate groups are attracting new members. That tie allows the hate groups to demand violence and criminal action from their followers, who he says are only too willing to do whatever it takes, feeling that they owe those who provided them affection and belonging.

After witnessing firsthand for a week how Nattiv directed actors like Jaime Bell (Rocketman, Turn), who plays Widner, through his story, he said that it plays out mostly like his real life. “The movie shows how groups can suck people in, but after ten years being in, I lost interest. I could see the hypocrisy, and I didn’t care about the politics as I was trying to raise a family. The rough cut I’ve seen, it took me four to six hours to watch because I just kept having to take a break. It was hard to watch because a lot of it hit close to home.”

After witnessing firsthand for a week how Nattiv directed actors like Jaime Bell (Rocketman, Turn), who plays Widner, through his story, he said that it plays out mostly like his real life. “The movie shows how groups can suck people in, but after ten years being in, I lost interest. I could see the hypocrisy, and I didn’t care about the politics as I was trying to raise a family. The rough cut I’ve seen, it took me four to six hours to watch because I just kept having to take a break. It was hard to watch because a lot of it hit close to home.”

“If I can prevent one kid from doing the stupid things I did, then I’ll have won. I just want to leave the world better than I found it.”

That possibility – for Widner to leave the world of the VSC, to turn from his violent ways, to make penance for his decade of crime and pain-inducing behavior – came when his then-wife Julie (Danielle Macdonald of Dumplin’ and Bird Box in the film) put him on the phone with the director of the One People’s Project, Daryle Lamont Jenkins, in a move Widner called an “okie-doke.” Unbeknownst to Widner, she had reached out to Jenkins, who had been stalking Widner as a candidate to “flip,” to help jump out of the same gang he helped create.

In the beginning of Skin, the audience sees Jenkins as Mike Colter (Breakthrough, Luke Cage) portrays him, engaged in a rally in opposition to white supremacists. Later, Jenkins videotapes Widner as he trick-or-treats on Halloween with Julie’s children, urging him to leave the VSC and his hate behind. Even as some African Americans urged Jenkins to avenge other atrocities against Widner, the ex-Air Force serviceman stood his ground for what could be.

“I would stand in the middle of a field if it would get one guy to leave!” Jenkins exclaimed. “When Julie put me on the phone with Bryon, we talked for hours about music, about the bands we liked. It wasn’t a ploy, but just getting to know the guy. I asked him what he wanted to do with his life because he was already in the direction of getting out. He needed a cheerleader, a sense of direction, and I was that for him.”

“I would stand in the middle of a field if it would get one guy to leave!” Jenkins exclaimed. “When Julie put me on the phone with Bryon, we talked for hours about music, about the bands we liked. It wasn’t a ploy, but just getting to know the guy. I asked him what he wanted to do with his life because he was already in the direction of getting out. He needed a cheerleader, a sense of direction, and I was that for him.”

Jenkins’ parents were both educators who cared about other people, helping them out whenever possible. His mother was a missionary through their church, and a nurse; his father was at times a drug counselor. The gregarious activist explained, “He would say we take human garbage and make a human being.”

The two teachers taught Jenkins the power of patience, of tolerance, and of a spirit to reach out to others. Those lessons motivated him toward an activist role extending out of Somerset, New Jersey, to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, P.A., and beyond. It’s his belief that racism will not last forever but it is real and part of our present reality that we must teach people to confront because it is embedded in our nation’s DNA. He hopes the film will shine a light on a real-world problem and that people who see it, specifically people of faith, will be moved to act.

“The audience should take a look at the young people in these hate groups. Their motivation doesn’t come from the same foundation as older people, who you could argue came from how they were raised. The kids you see in Charlottesville or Dylan Roof (Charleston, S.C., shooter documented in Emmanuel) come from an experience of not believing that lives matter. We need to minister to them, to reach out to them before other people, the wrong people like white supremacists, gangs, or radical cults do. Because when the wrong things happen or they’re left until the wrong devices, they answer their questions with their own answers.”

Jenkins went on to mention the young white man at Charlottesville who was chased down by a group of protesters after a young woman was run over in August 2017. When the group caught up to him, he tore off his shirt, and told them he wasn’t a white supremacist but he was only there to have fun.

“You’re really disconnected from reality if you think this is fun,” Jenkins continued. “Someone died.”

Thanks to Widner’s change of heart and the intercession of Jenkins, Widner’s life continues. Two men from separate, disparate beginnings whose stories are now intertwined forever, from stains that run deeper than the ink of Widner’s tattoos or the tone of their skin. Two men who see the world as it is, who hope for the world as it should be, and who will continue to struggle against the forces of hate.

Because every life matters.

Skin is in theaters and On Demand on July 26.