By Jacob Sahms

By Jacob Sahms

There are so many problems with “best of” lists. They’re subjective; the proximity to the writing of the list impacts how films are remembered; the audience the list is prepared for receives each list differently. But 2020 is such a weird year to consider, with the cinematic industry shut down in terms of production AND in releasing films. And yet, there are films I believe have something to say about the world we live in and the world we’re supposed to be helping usher in through the kingdom of God. So, in chronological order of release date, here are the ten best films I watched in 2020.

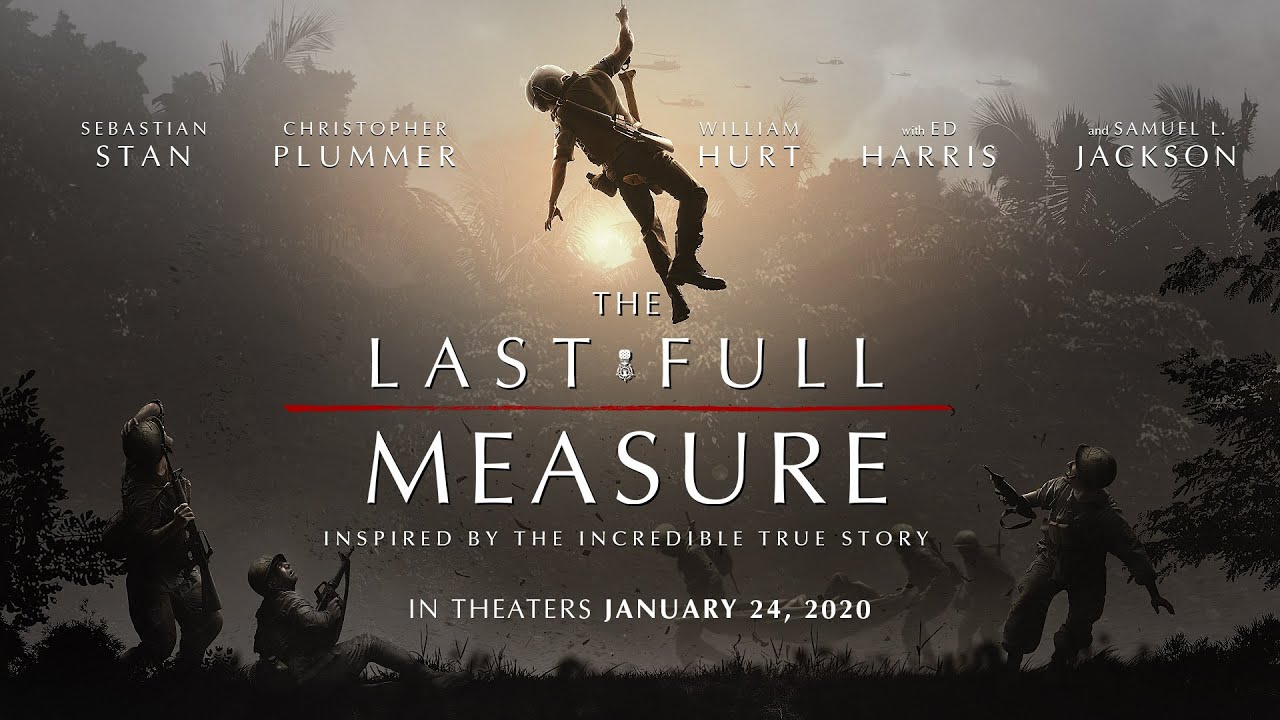

The Last Full Measure (January)

In the ways that A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood was more about Fred Roger’s impact on reporter Lloyd Vogel than it was about Rogers himself, The Last Full Measure shows how Pitsenbarger’s parents (the always excellent Christopher Plummer and Diane Ladd) and the men served with and even saved (Samuel L. Jackson, Ed Harris, Peter Fonda, William Hurt) are still impacted by his bravery. And it shows how a fictionalized bureaucrat (Sebastian Stan) comes to understand morality, truth, and brotherhood thanks to the example of the soldiers who survived the war. That’s what left me crying.

Have you ever considered what impact your life has on those around you? If you disappeared, what (or who) would be different for you having lived and died? What have you or I contributed that would make others fight for thirty-four years so that you could be remembered correctly, or considered at all? As Christians, the question isn’t so much about how we would be remembered but what our eternal impact would be. Would there be those who had contributed to your life but who had been so touched by your faithful life that they were yearning to be reunited in heaven? [For more, click the link above.]

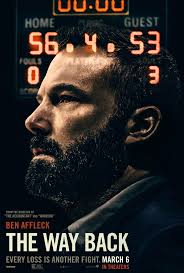

The Way Back (March)

The Way Back (March)

While films like Coach Carter show the ways that a coach can ‘save’ a team or a disparate group of student-athletes, The Way Back shows the impossibility of overcoming addiction without real investment on the part of the addict or the involvement of people around the addict who care enough to love him or her through the uphill climb. Sure, Cunningham (Ben Affleck) has a sharp basketball mind that impacts the win totals of his team, and increases the confidence of the team, providing positive on-court results and even providing him a sense of peace. But Cunningham is a problem, a moment, a reminder away from having his success throw him back into chaos. He simply doesn’t have an anchor to hold onto.

Early on in the film, the team’s chaplain challenges Cunningham to adapt his language to meet the Catholic school’s ethics code. Cunningham asks the priest if he really thinks with all that’s wrong in the world that “someone up there” cares about the language he uses coaching a basketball team. The priest continues to encourage Cunningham moving forward to be like Jesus, even as the coach struggles with his inner demons and the addiction writhing under the surface. [For more, click on the link above]

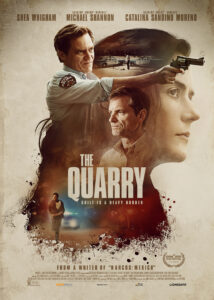

The Quarry (April)

The Quarry (April)

This Damon Galgut story, adapted by Teems and Andrew Brontzman, crackles cinematically like a Flannery O’Connor or William Faulkner novel brought to life, or the more contemporary version of southern gothic told by Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water). The camera allows us to see the desolation, the brokenness, and the hopelessness of the area, primarily in the Spanish-speaking community represented by the preacher’s landlady, Catalina Sandino Moreno’s Celia and her cousins, Valentine (Bobby Soto) and Poco (Alvaro Martinez), who are growing marijuana and stealing to make ends meet. With Shannon’s Chief Moore constantly looking for “mud to clean up off the streets,” the new preacher isn’t safe, but the racist assumption by Moore is that the Spanish-speaking community is always at fault (even while he sleeps on the sly with Celia).

The film is certainly intended for mature audiences thanks to the vocabulary and a few bursts of intense violence. But the reality is that Teems’ translation of the story focuses in on the way that faith and life are always finding themselves in the quarry – wrestling and grinding against each other, emerging bloody and bruised – and the winner is not always clear. In an Old Testament-style parable set in the dirt of America, the scriptural overtones are never far away, even if we’re not beaten over the head with them. [For more, click on the link above]

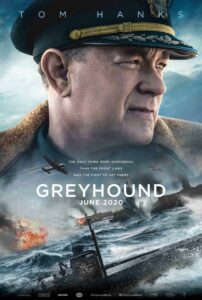

Greyhound (July)

Greyhound (July)

When we meet Commander Ernest Krause on the Fletcher class destroyer, USS Keeling, he’s praying Luther’s prayer from the Small Catechism, “Let Your holy angel be with me, that the evil foe may have no power over me. Amen.” He’s a spiritually deep man who tells a pair of his sailors to repair their broken relationship (they were caught fighting) so that it will give him peace, whose quiet morning blessing over his cup of coffee brings quiet to the galley, whose quotation of Proverbs 3:6 results in a dangerous play to discover a hidden U-boat (against the expectations of his crew on the bridge). Pursued by German U-boats in the midst of the North Atlantic, Krause’s faith – and calm – stand between his men and a miserable, watery grave, as he serves as a defender for ships crossing the Atlantic.

Krause is the character first composed by C.S. Forester in his 1955 World War II novel The Good Shepherd, written for screen by the legendary Tom Hanks, and depicted here for AppleTV by Hanks himself. The character isn’t the sure strong leader of old school military films but one who second guesses himself in his first major command, who cares deeply about the wellbeing of his men, eschews examining the results of a “kill” for returning to post to protect the convoy, and mourns the passing of souls, even if they’re the enemy Krauts he’s supposed to be defeating to win the war. Should we be surprised? [Click on the link above for more]

Boys State (August)

What follows over two hours is a film by adults about teenagers acting like adults, who as politicians, sometimes act sophomoric. It’s not a horror movie, but it could be! As the students are slowly sifted through, following a handful of them more closely as they close in on election, the audience sees the way that the students believe (or don’t believe) what they’re saying. Some of them change their views to match their party; some of them change their words to get a greater response from those who will vote. It’s art catching life imitating adulthood.

The film won the Grand Jury Prize in the U.S Documentary Competition at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and is wildly compelling, even for someone (me) who isn’t interested in politics for politics’ sake. The young men are incredibly earnest – even when they’re playing a part – and it’s wild to consider that their partially formed understanding of politics is based on what they’ve seen adults, even their parents, do. So if it’s chilling ….? [Click the link above for more]

Love & Monsters (October)

Against the recommendations of the leaders of his colony, and against incredible wildlife odds, Joel sets out across the eighty-five-mile gap between the colonies. “Run fast, and try to hide. Don’t fight,” the group recommends, when Joel proves intent on leaving. He emerges from his War of the Worlds/Lost-type bunker to breathe air for the first time in seven years, with a trusty map, a crossbow, and an optimism that defies everything we’ve seen about Joel in the first fifteen minutes of the film. He doesn’t even know which way he is supposed to go from the bunker!

O’Brien plays Joel with a winsome earnestness, providing amusing voiceovers in his “letters” to Aimee. Sure, it’s horrific when a giant toad tries to lasso Joel and eat him, but an adorable dog that Joel creatively names “Boy” comes to his rescue. Together, they are rescued from giant worms by two experts in the apocalypse, Clyde (The Walking Dead’s Michael Rooker) and his child companion, Minnow (Ariana Greenblatt). Rooker provides some hilarious wisdom (and criticism) in this stage of Joel’s journey, a sort of coming-of-age, survival, romance mash-up, with a dash of monsters thrown in for good measure. [Click on the link above for more]

Let Him Go (November)

Let Him Go (November)

Kevin Costner has always looked comfortable in westerns. Whether it was the historic Dances with Wolves or the modernized Yellowstone series, his way seems content with the way of the cowboy. In director Thomas Bezucha’s adaptation of the Larry Watson novel of the same name, Let Him Go, Costner is a retired sheriff-turned-horse rancher named George Blackledge who finds himself in a conflict over his toddler grandson. But his knowledge of the way the world works only serves as a warning of the storm that’s coming.

After their son dies, Blackledge and his wife, Margaret (Diane Lane), mourn, but their sorrow is doubled when their daughter-in-law, Lorna (Kayli Carter), marries Donnie Weboy (Will Brittain) and moves out with their grandson. When Margaret witnesses Donna abuse Lorna at the grocery store, and the couple moves back to where the Weboy clan lives, Margaret is determined that they will go and rescue their grandson. Arriving in the outskirts of civilization where the Weboys live, the Blackledges find that Donnie’s mother Blanche (Lesley Manville) and uncle Bill (Jeffrey Donovan) rule the area with intimidation and violence. After a vicious collision with the Weboys, the Blackledges are faced with a choice: will they give into the fear that everyone else seems to have for the Weboys or will they find a way to fight back?

Songbird (December)

Songbird (December)

The year is 2024 and COVID-19 has mutated, leading to absolute, militaristic lockdown. Bike courier Nico (I Still Believe, Riverdale) rides around the city freely thanks to immunity to the disease, while his girlfriend Sara (Sofia Carson) waits expectantly for the day when they can vacation outside of the city. When Sara is exposed to the virus and hauled off to one of the state-run Q-Zones, akin to concentration camps, Nico goes after her, risking everything.

Songbird comes across like a disaster film, a la World War Z or something similar, but in reality, the worst elements of this 2024 world are humans. Human greed, human violence, human control, mostly embodied by Peter Stormare’s head of Los Angeles ‘sanitation.’ By sanitation, the film means that the government has monetized the acquisition of immunity bracelets, marking a person safe to travel, like the selling of indulgences prior to Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. In reality, the bracelets provide safe travel but not actual protection from the virus. And yet, even while people are struggling with living in a state of fear and illness, others are trying to find ways to profit.

Wonder Woman 1984 (December)

Wonder Woman 1984 (December)

Can a person pursue everything they ever wanted at all costs? What are the costs of getting everything that you want or hope for or … think you need? What happens if all of the suffering we’ve endured could be wiped away with a wish, if all of the hardships we endured could be justified by the end result? Ultimately, that would provide purpose in situations where purpose seems alien, and answer questions that I’m not sure we’re meant to know the answers to this side of heaven. The reality is that God doesn’t promise us happiness or success, but the encouragement to be faithful, and to trust.

Wonder Woman 1984 again calls to mind John 15:13 but even more so, the sequel calls for a sacrifice of self that takes it deeper than trite verse picking. Instead, it asks us to consider what about our lived lives is sacrificial, not just the lives we would give up in a moment to save someone else. Jesus said, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit them if they gain the whole world but forfeit their life? Or what will they give in return for their life?(Matthew 16:24-26)” [Click on the link above for more]

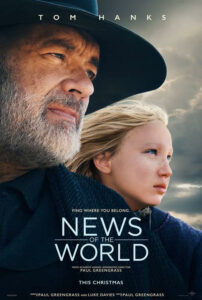

News of the World (December)

News of the World (December)

Director Paul Greengrass (Captain Phillips, United 93, Green Zone) has shot the film in earthy tones that make Hanks’ role both everyman and tied to the world through which he rides. Inside light is dark, natural to what the world of the mid-1800s looked like, and outside isn’t much better — just a spray of dull browns and grays… except that in the distance, the sun always seems to be shining, never quite here but almost. Through this world of knowledge and light Kidd rides, hoping against hope to be the kind of uplifting leader he once thought possible.

Of course, there is danger in the wild, but in an ironic 2020 twist, the violence and barrenness of nature is no threat compared to that in the human heart. While various people, set against the post-Civil War element, speak of truth, justice, and a way of peace, Kidd and Johanna find that too few of their fellow citizens can lay aside their basest instincts to help each other. [For 2020’s sake, COVID-19 serves as a deadly, unseen thing, but in reality, humans continue to do more damage to each other by their words, actions, and in-action than all of the diseases in the world.] We’re sure that Kidd has done things he wouldn’t have outside of war, that he lives with regret, but in Kidd, we see a man who longs to protect the future – embodied in Johanna – from the evil and violence he has seen. [Click on the link above for more]